By Hayden Gillooly (S’19)

Hayden Gillooly is an alum of Williams College, Class of 2021. She now works as the Assistant Director of Admissions for Overland Summers.

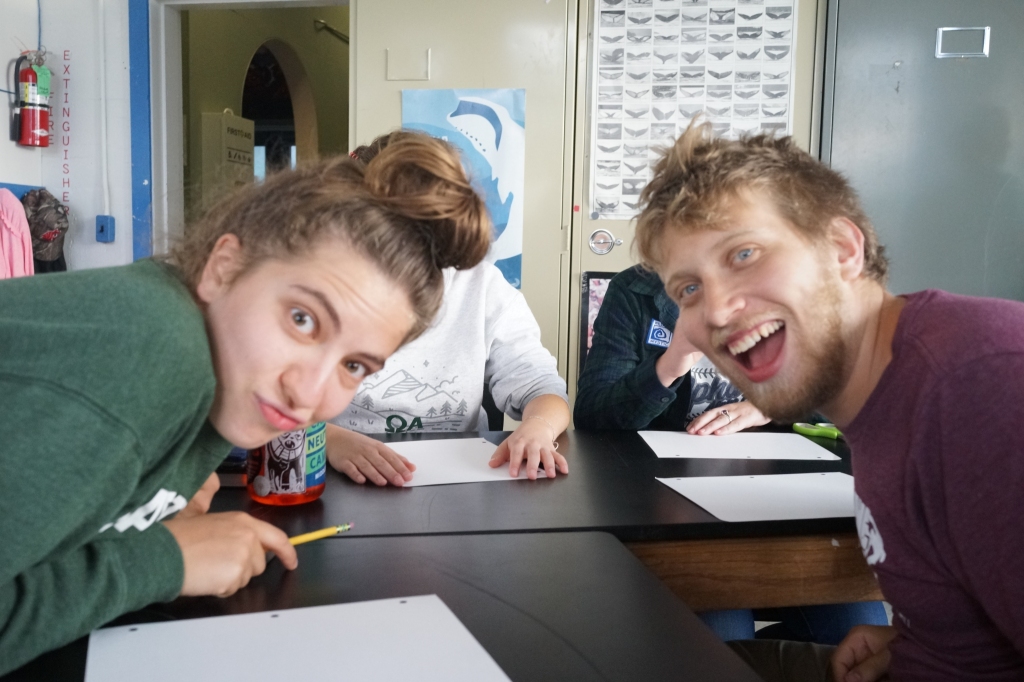

In Zach Arfa’s (F19) senior year at Oberlin College, he received an email from Williams-Mystic asking if he wanted to study the ocean. The program sounded so neat, that Zach wondered whether it was real. He researched the program, applied, and was enrolled within a week. As a Dance and Psychology double major, Zach brought a unique perspective to his Williams-Mystic semester, intersecting the arts with science.

My conversation with Zach covered everything from his experience catching salmon with his bare hands during his Williams-Mystic Alaska field seminar, to understanding climate-related trauma through a psychological lens. I could have listened to Zach talk for hours—his face lit up while leapfrogging between topics. I felt like a student in class with a favorite professor, furiously writing down notes—trying to capture it all— and completely captivated by the energy that Zach emits.

For the last few years, Zach worked at the Hilltown Youth Recovery Theater, doing movement and circus arts with teenagers who are overcoming trauma and addiction. Now, Zach is currently working for Americorps through a disaster relief program. He was deployed in Louisiana, and then in Texas, and recently moved again to Kentucky to help rebuild and do mold remediation. I was immediately curious to hear about what it’s like to enter communities whose infrastructure has been ravaged by natural disasters. “They said that if you’ve seen one disaster, you’ve seen one disaster,” Zach said, matter of factly. Each situation is unique. There is little separation between one’s work in this field, and their “off” hours, since so much of the experience requires workers to live in the disaster zone, too. Zach and his coworkers were living in an RV, eating frozen meals, and working 12-14 hours six days a week.

Zach explained how stress is, at its core, a physical process. “It lives in our bodies”—with tension and electrical signals. We often think of stress as a “cognitive and emotional thing,” however, “it’s kind of nebulous (in our colloquial understanding), even though we all feel it.” It sometimes feels all-encompassing, when in reality, there are pinpointable components of stress within us. Perhaps it’s in our tensed shoulders, or locked jaw. Studying dance in conjunction with psychology has allowed Zach to “reconceptualize it [stress] as this physical sensation.”

For Zach, movement—in both big and small ways—allows him to reconnect with his body even in the times of most intense stress. This is especially important when Zach is “engaged with situations where the stakes couldn’t be any higher,” such as working on the frontlines of disaster relief. Zach shared a strategy that one of his dance professors uses during times when she is busy and overwhelmed with deadlines. It’s not necessarily about big, grandiose movements—it’s about “feeling the weight of the library doors while entering and tracing the little pen movement that creates vibrations, or the weight of the lawn mower.” Zach believes that “attention to these moments of our day that we take for granted can be that respite.” Since chatting with Zach about this technique, I’ve integrated into my own life—being intentional about noticing the feeling of the snow crunching beneath my boots, and my fingers tapping on my keyboard. Our bodies are a miracle, really—our heart beating and lungs filling with air, without us asking them to. Savoring these small touch-points feels like an expression of gratitude.

As two Williams-Mystic alumni, our conversation naturally shifted to focus on environmentalism. Approaching climate studies from a psychological lens, Zach wonders “how do you face an existential crisis in the face and not get paralyzed?” He discussed recently listening to the podcast Drilled, which dives into the cover-up strategies of the oil industry, and explores just how much these companies knew and know. Zach explained how the companies’ strategies are to put the blame onto consumers—to make us feel as if all of the environmental degradation is a result of the inaction of individuals. This feeling is engrained “deep in us, and fits in with a culture of individualism—it’s the American myth that we think we’re strong individuals.” When, in reality, it is the systems set up by those large companies that are responsible for the climate crisis. In other words, it’s not the fact that you drive your car to work every day, but the fact that the only way to get to work on time is to travel on roads with a certain speed limit and vehicle type requirement that only cars fulfill, and no other option is easily available. The strategy of the anti climate change action organizations is to “dilute the issue to make it seem like individuals in isolation can do anything.” We need to be thinking about systems; not just how we get better cars, but how we get better roads. As we grapple with the emotions related to climate change Zach said that “we don’t need to feel the guilt and shame as strongly as we do.”

Strong approaches to addressing systemic issues must be rooted in building connections. “It’s too much to put on ourselves. We need to hold this [trauma and stress] together,” Zach explained. And processing these nuanced and complicated topics together isn’t about “getting rid of the hopelessness and fear,” because all of our emotions are valid. It’s about holding these feelings together through all of the trials and tribulations of our changing world.

After the Williams-Mystic Louisiana field seminar, Zach felt overwhelmed by the magnitude of struggles that Lousianans are facing as a result of climate change. In Zach’s time processing his role in these large-scale issues, a quote attributed to 16th century theologian, Martin Luther, stuck with him. Martin Luther was asked, “What would you do if you knew the world was ending tomorrow?” Luther replied, “I would plant a tree.”

Whether it be helping to pick up the pieces after a natural disaster, or working with young people to spark their joy and enthusiasm about movement and dance—the work that Zach is doing certainly plants seeds of change. Zach explained how the work “doesn’t have to be huge and dramatic. It just has to be engaging, and feeding that sense of purpose to do good work.” Knowing that special people like Zach are ‘planting trees’ for our future makes me feel hopeful about the world that we live in.