By Ruhamah Tess Weil

Ruhamah is a junior at Middlebury College and a proud member of Williams-Mystic F’19. She is majoring in Film and Political Science and hopes her academic experiences will inform a future career in socially-impactful storytelling. She was born in Washington, D.C. and moved to Switzerland when she was five. There, on the banks of Lac Leman, she discovered a love for nature and all things water. She is unabashedly obsessed with dogs and books and Netflix and tacos and art (of any form) and coffee. While at Williams-Mystic, she became a yoga fanatic and much, much more determined (than she already was) to learn how to surf.

This piece is one of several examples of research conducted in the Williams-Mystic Marine Policy class. Ruhamah conducted her research in collaboration with Chief Shirell Parfait-Dardar of the Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw. Chief Parfait-Dardar is one of our main hosts and co-educators on the Louisiana Field Seminar.

Click here for more example of how Williams-Mystic students engage in research on timely, real-world issues.

—

There is nothing noticeably blue about a cooked Louisiana blue crab. Lying belly up on the table, its legs curl inwards like the talons of a raptor, its prey having just slipped free of their grip. Boiling water has turned its formerly indigo carapace a feverish orange. Against the milky white of the abdomen, this vibrance appears to bleed, as though something beneath the shell is still alive, trapped and fighting to break through its confining armor. To anyone unfamiliar with the dish, the blue crab is a formidable opponent. If not removed correctly, exoskeleton cracks and splinters, blurring the line between edible and inedible. Buttery meat hides unpredictably within claws, easily overlooked. Internal anatomy unrecognizable to the common inlander—stringy, spidery, sometimes green—challenges the desire of eyes sanitized by pre-prepared foods. Eating the blue crab is not intuitive, is messy, is delicious. But it is not something a fork and knife can dissect. It is not something you can simply figure out as you go along. You have to be shown how by those who know.

“That’s what’s so unique about us: our cooking.” Shirell Parfait-Dardar, Chief of the Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw, does not sound like someone who’s had a hard week when she says this. She laughs, and it sounds genuine. “It’s just so unfortunate that we’re losing what we cook with, you know?”

Southern Louisiana is one of the most popular fishing destinations of the United States and is the nation’s second largest seafood producer, with an output of over 850 million pounds of seafood per year. The cuisine that characterizes the Gulf of Mexico has never been associated with restraint or subtlety. This is the home of Mardi Gras, of “Slap Ya Mama” Cajun seasoning, of the Po’boy, of the deep-fried, sugar-smothered, steaming beignet. And yet, with every passing year, the plates of coastal Louisianans are growing just a little smaller, just a little emptier.

The term “food desert” seems unusually cruel when applied to Terrebonne Parish in southeastern Louisiana, for of all the things the region is lacking in—funding, healthcare, social justice, and higher education, to name a few—water is not one. It is an uncomfortable truth that the bayou has become the butt of many a morbid joke. “I’ll be traveling south next week—that is, if it’s still there!” Land loss is not a debatable issue in this place. It is happening, happening visibly, and happening at rates that would seem astonishing in most other regions of the country. The popular fast fact is that every one hundred minutes, a football field’s worth of wetlands disappears into the ocean. Here, houses live on stilts. You don’t park your car at the very edge of the road—that is where ditch becomes moat and sinking mud masquerades as solid ground. Prized possessions sit well above those belongings you don’t mind gifting to the flood. Tall rain boots are kept within reach.

Flood control and water diversion projects all along the Mississippi River’s path have narrowed and sped up water flow, directing it straight out into the Gulf. Mark Twain, that authorial embodiment of the Mississippi, once described his relationship to its geography as altered by his becoming a steamboat pilot. “Now when I had mastered the language of this water and had come to know every trifling feature that bordered the great river as familiarly as I knew the letters of the alphabet, I had made a valuable acquisition. But I had lost something, too. I had lost something which could never be restored to me while I lived. All the grace, the beauty, the poetry had gone out of the majestic river!” Although his attitude towards the waterway is clearly a tender and loving one, it equally echoes the belief that emerged in accordance with the systematic engineering of the river’s path in the nineteenth century: that the basin was a sedentary fixture of the landscape, that it could be tamed, confined, and memorized, that it wasn’t an evolutionary body subject to interminable change. This myth has resulted in the robbing of Louisiana. Sediment amassed in each state the Mississippi flows through should be deposited in the delta, where river becomes ocean. This sediment would, if left to nature’s own devices, be incorporated into the wetlands of Louisiana, strengthening and aiding the retention of a land that is at the constant mercy of erosion-causing wave energy. But this is no longer occurring.

In state, the structures impeding this process are there as urban protective barriers, keeping New Orleans dry. And after the devastation of Hurricane Katrina, even those who now are holding the short end of the stick repeatedly say it’s okay, we get it. But Dr. Craig Colten, professor of geography and anthropology at Louisiana State University, is not surprised by the sociopolitical parameters of this dynamic, explaining that the flipside of the understandable choice to protect the city is also a historically charged decision to ignore those rural communities on the southern coast. “Most of these people came in various diasporas, came in less than ideal circumstances, pushed out to the margins of society as well as to the literal edge of our continental land.” For that reason, he’s determined to shift the public perspective of the issue. It is not merely an environmental crisis, but a crisis of society too. “There’s lots said about coastal restoration,” he says, “but nothing is said about coastal culture restoration.” However, in order to restore something, it has to have been lost first.

“My mother remembers community gardens down in Dulac. She remembers when you really didn’t go to the doctor: you went to my great grandmother. She was a healer, and she did it all naturally.” Chief Parfait-Dardar is speaking of recent times—of her own lifetime. Today, because of a lack of space for gardens due to acute land loss, because of saltwater intrusion as a result of wetland destruction, traditional foods and medicinal plants can’t grow. “We’re an oil and gas state. There’s tons of pollution of the water, of the environment.” Although she would be the first in a room to stand up and decry the death of vegetation in her town, she isn’t ready to say that it has been lost. That’s thanks to her kids.

“We teach [the next generation] hands-on how to plant, protect, preserve, and then utilize. We teach them that everything works together.” The order of those lessons is crucial to proper stewardship. Even if there is no current planting or harvesting happening on the lands of the Grand Caillou/Dulac Band, they are hopeful and perseverant. They keep the knowledge alive through sharing.

On the other hand, the tribe is realistic. Careers are no longer expected to be in the fields that have traditionally supported them. Subsistence living is totally out of the question too. Not that long ago—until Hurricane Andrew of 1992 pushed environmental stressors over the edge—families could raise livestock, chicken and goats, could hunt for meat, deer and rabbit, could fish and grow produce. Today, you need an income. You need to pay for your flood insurance and for your groceries and for your electric bill so you can freeze most of the groceries (to hold you over until you can spare the time for another shopping trip) and for the car that you need to drive to get to the groceries and the bank and the doctor and the pharmacy at least fifteen miles away.

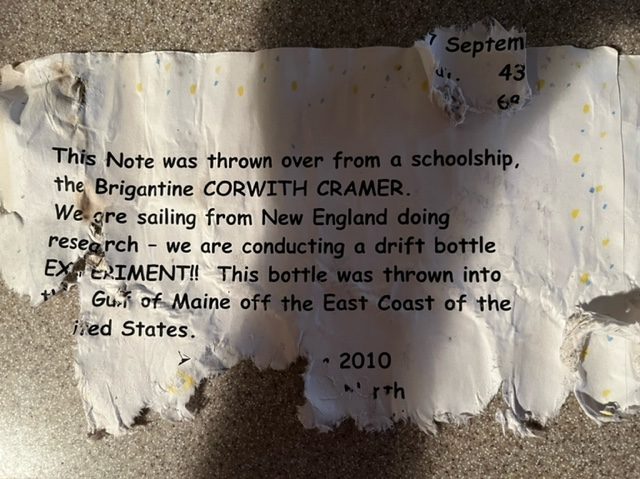

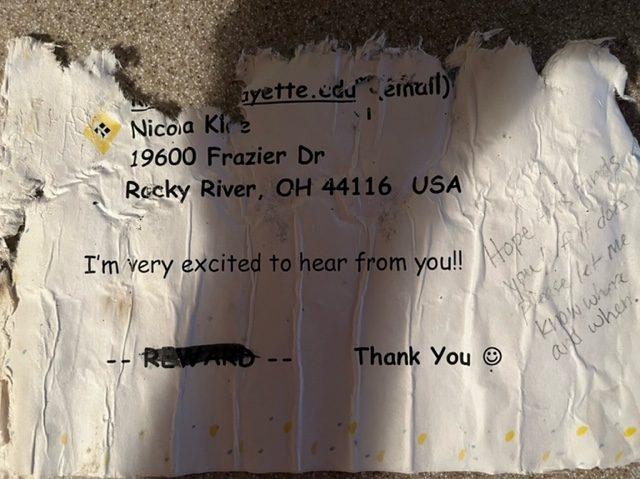

If you worked in the area in 2010, you remember the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill. “Pardon my language,” Chief Parfait-Dardar warns, “but Deepwater kicked our asses and it’s still kicking them today.” Many of the local fishermen don’t even break even because of how steeply catch and quality of catch has declined since the disaster—and they certainly can’t afford to keep any to feed their own.

The chief, like Dr. Colten, argues for the young to migrate north. But critically, she does not envision this as a permanent move. She wants the young members of her tribe to go and educate themselves on things that have not yet found a place in southern Louisiana, such as green energy. “You may need to leave the state to get the proper training but bring it back. Just because it’s not here doesn’t mean you can’t bring it back.” Over and over again, Dr. Colten warns against disaster dispersal: unorganized migration north following disaster. However, due to the dire living conditions and degrading environment of the present, virtually any migration could be defined as disaster dispersal. According to Dr. Colten, NGOs working for the area despise the idea of migration. They call it “retreat” and they “spit it out like the term is toxic.” Dr. Colten underscores how geographic mobility, coupled with the transportation of culture, is key to the very character of the people of Terrebonne Parish. Many residents here came from elsewhere and recreated their communities in the bayou.

Chief Parfait-Dardar acknowledges her adaptive roots and stresses once again the role formal training has in future evolution. As the bayou fails to support careers, people head to the nearby city of Houma for business opportunities. But those aren’t common for Native Americans, who often lack access to the formal business training needed to succeed.

“Right now, the adaption hasn’t worked,” Chief Parfait-Dardar says. “We’ve had to turn to grocery stores, and we can’t pay for organic diets. ‘Yucky’ foods are the least expensive, are what we can afford.” This has led to rampant cancer, diabetes, and heart disease in her community. Relying on the safety net that is currently in place hasn’t meshed with her community’s way of life either. SNAP benefits, the food assistance program many in the area partake in, come with stringent work requirements. For many tribal community members — the elderly, those who lack GEDs, and those who were trained in fields that are no longer viable due to environmental devastation — these work requirements are nearly impossible to fulfill. While adaption is accepted as the way forward, it won’t save them if only Chief Parfait-Dardar’s tribe evolves. Serious rethinking and adaptation of local, state and federal efforts is needed too. The first step towards this goal may simply be a shift of mindset.

As inspiration, Chief Parfait-Dardar offers a traditional Native proverb, “The land was not given to us by our ancestors, it was loaned to us from our children.” There is a moment of silence between us and then she says definitively, “If more people understood that concept, we wouldn’t be in the state we are in today.”